| Strategy | Luck |

|---|---|

| Interaction | Components & Design |

| Complexity | Score |

Shakespeare: The Bard Game – note the pun in the title, that’s what made me decide to buy it – is not so much a game for boardgame enthusiasts with an interest in Shakespeare, it’s targeted at Shakespeare enthusiasts with an interest in boardgames. What gives me that impression, you ask? For one thing, it employs a roll-and-move mechanic that has fallen out of favour for serious boardgames. Moreover, it has a heavy trivia component, another thing many boardgamers frown upon, about – you guessed it – Shakespeare plays and the trivia questions in this one are tough, definitely more appropriate for experts than amateurs. But if that was all, what we would have on our hands here is a Trivial Pursuit with a narrow subject for the questions and it wouldn’t have intrigued me enough to buy the game on the spot.

And indeed, there’s more to Shakespeare. Those things are embedded in a game set in the bard’s own time and cast each player as the head of a start-up theatre troupe playing on stages around London to win acclaim with the fastidious audience. And so they roam around the city, gathering all they need to stage a play. Movement is determined by the roll of two dice, but this is only the maximum move, you may stop at any point before. If you roll doubles, you have one additional turn after this one. If, on the other hand, you roll the letter f that replaces the sixes on these dice, you draw a fate card. Fate cards have a fifty-fifty chance to either help or hinder you: they may award you a fistful of shilling, cost you some shillings, imprison one of your actors or make you lose your next turn.

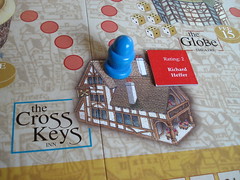

With your roll, you move around the city of London. Important locations are scattered on the map and sooner or later you will want to visit all of them. For example, you may visit the master himself in his chambers and gain first access to his latest masterpiece for a generous donation. Or you may find he produced one of his less successful plays, but as you’re drawing a play randomly you have no way to know in advance. Once you have a script, you will most likely want to play it for an audience, but you need some preparation first. Actors are obviously useful in staging a play, and – the acting profession may excuse me for saying this – the obvious place to look for them is at an Inn where you may hire one actor per turn. Some modern plays may be content having only actors and nothing else, but this is not modern: you need props and costumes, and you buy them at Leadenhall Market, all the way to the right on the board. Finally, some plays require you to have the support of one or even two patrons which you gain at the Great Houses – you can always gain one patron there, but if you impress them with your knowledge – answer an easy trivia question – you can gain two patrons on one turn.

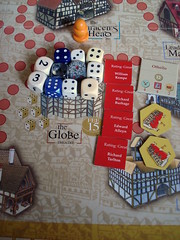

And after all that, when you finally collected enough actors, props and patrons, it is finally time to lift the curtain at one of the four theatres. There’s nothing more to it than paying the theatre’s fee and adding up your acclaim points, really. The theatre you play at lets roll from one to five dice for points, the script adds six to twelve points, each actor adds another zero to three points – except when it’s a great actor, those let you roll another dice instead, as does every patron tile used on the play. All in all, you can gather eleven dice to roll for points, with only two included in the game. Having eleven dice in the box would be overdoing it, but five or six would make rolling for points less tiresome.

You may have noticed that I talk a lot about paying for things but say very little on making money. Money doesn’t come, as you might expect, from staging plays. Instead money is made using the other possible action at the theatre: answer a trivia question for 10, 15 or even 20 shillings. As stated above, the trivia questions are tough. Or would you know which play has the line “Thy lips rot off!” without asking Google about it? Granted, that was one of the difficult questions. Lets go with an easy one instead. Which of these comedies was the earliest: “Twelfth Night”, “The Comedy of Errors” or “As You Like It”? All questions are multiple choice, but they are still hard. Fortunately, that doesn’t mean non-experts are dead and buried. Instead of answering a question, you can chose to recite one of Shakespeare’s famous speeches – read from a card, not from memory – for up to ten shillings. Not quite as profitable, but it allows you to play with the Shakespeare buffs. Finally, you may put on a play in the streets, an activity known as busking, and make 5 shillings from passers-by’s donations. Additionally, busking forces you to draw a fate card.

One more option when walking around London that I omitted so far is an encounter with another player. In that case you may trade, brawl or flirt with them, but all of them end with some kind of resource finding a new owner. The reasons I omitted this option so far are simple. The situation rarely arises because the board is pretty big, you’d have to go out of your way to intercept another player to make use of these options. With the chance of encountering another player, you rarely profit from these encounters: it’s just to unreliable as a source of something you need to stage your play, so you make sure to have everything with you, anyway. On the other hand, taking something from another player can have a very destructive effect on him: force him to walk back to Leadenhall Market to replace the prop you stole, for example, may cost your victim a few turns, it’s a long walk there. We considered that unbalanced enough that, even when we had the chance, we rarely made use of it.

The game ends in a rather unusual way: after 60 minutes, everyone takes one last turn and then the player with the highest Acclaim wins. Now I won’t say that in those 60 minutes we didn’t have a good time, because whenever we played Shakespeare: The Bard Game we did enjoy ourselves. But looking at it from a boardgame perspective reveals a couple of deficiencies. The movement around London stands out as one of those. I’m not against roll-and-move games in general, but here you spend too much time between locations: going from one to the next can take you three turns if you are unlucky, and apart from taking a chance with busking those turns are wasted. Even more frustrating when everyone else is taking additional turns from rolling doubles and passing St. Paul’s Cathedral. And the influence of luck doesn’t stop there. Some players can busk every turn, gain additional money from a favourable fate card and finish the game with money to spare without ever answering a trivia question. Others lose actors to the fate card every time they gathered enough to finally start the performance or miss three out of six turns. And if that’s still not enough, putting on a play involves many dice and the difference between one great roll and a horrible one can easily mean enough points to decide the game.

For my taste, luck has a too big influence on the outcome of Shakespeare: The Bard Game and if you’re approaching it as someone interested in boardgames, consider yourself warned about that. If you’re looking for an interesting gift for the theatre geek in your life and don’t mind playing it with them, then you might want to give it a shot. Who knows, maybe it awakens his or her curiosity for boardgames.

See my BGG post offering a variant that ditches the roll-and-move mechanic for a worker placement mechanic, ala Agricola. Also adds two new locations and some additional wrinkles that should speed up the game play considerably and add some new interest to the game without messing with the theme or basic content too much.

Gamerbut

Hello Gamerbut,

sorry for the late reply to your comment, we had the South Tasmanian Alligator Flu in the Meeple Cavelast week and were completely out of it. I just read your variant (link for the lazy: http://boardgamegeek.com/thread/1032108/a-new-way-to-play-shakespeare-the-bard-game ), and I’m quite intrigued by it. That’s basically a full rebuild of the game, and the result does sound like something I’d much rather play. Great job!

Thanks for reading my variant idea and for taking the time to respond.

Like most people, I dislike the simple roll-and-move mechanic, especially in games like this one, which seems to invite the players to simply wander aimlessly all over the board until he has gathered enough of whatever to accomplish something. I don’t like the idea of getting an extra turn for rolling doubles either, nor having a location on the board which serves no earthly purpose (the Gallows).

As a retired English teacher and long-time lover of Shakespeare, it in near impossible to get gamers to try this game with me, but the limitations I just mentioned make it a mere pipe dream for me. That’s why I recorded this idea. I hope one day soon to talk a few of my gamer friends into trying it with me, but gamers who also love Shakespeare (or at least are not intimidated by the Bard) are hard to come by in small central Minnesota towns. So are gamers willing to try something that is “basically a full rebuild” of a game that they know nothing about. BTW, I have typed a fuller description of the variant which I’d be happy to share, if you’re interested.

Note: Ask me sometime about my full rebuild of Avalon Hill’s “Assassin,” probably the worst game AH ever made.

One last thing. I sure would like to have a taste of that South Tasmanian Alligator Flu mix.