| Strategy | Luck |

|---|---|

| Interaction | Components & Design |

| Complexity | Score |

Concordia is, in the widest sense, a deck-building game in that you start with a set of cards and buy more cards as part of the game. But that’s where the similarities to games like Dominion or Thunderstone end. In Concordia, you don’t have to rely on the luck of the draw, you always hold all cards you haven’t played yet in hand. Every turn you play one of your remaining cards and perform its action. Now that we have the basics covered, we can go into details of the rules. That’s right, the game flow can be summed up as “it’s your turn, play a card”. But that would be oversimplifying the game a bit, the real fun is in what those cards do. We need something to do with that huge, pretty Roman Empire game board, its 30 cities and all those other materials still.

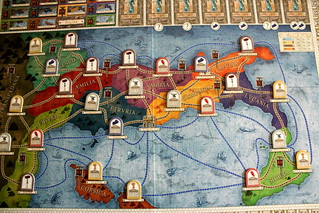

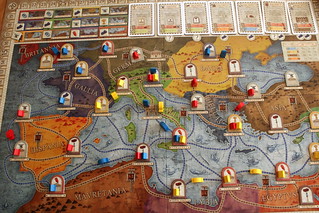

That’s exactly what those cards do, they let you do something on the game board. The Architect, the most common card to open the game with, lets you move your colonists around and build houses in colonies. Your colonists come in two flavors, land and sea colonists, that move on different paths on the board (quite obviously) but can all build houses in the cities at either end of their current path. The price you pay for those houses depends on the type of goods the city produces: bricks, food, tools, wine and cloth, with bricks being the cheapest to get and cloth the most expensive. Building always costs some goods and some money, and even more money when you’re not the first to a city, because then you pay the money part of the price again for each house already there.

Once you have a house or two – you can’t afford more with the goods you start the game with – you can use a Prefect to make them produce goods. Playing a Prefect, you choose one province and all houses there produce their goods, your own as well as your opponents’. But as the one who played the Prefect you also get the province bonus, one additional item of goods, and then turn the bonus marker over. This indicates that the same province can not produce goods again until someone uses their Prefect for his other use: flip all bonus markers back and take an obscene amount of money, but no goods at all.

If you need some goods that your own cities don’t produce, or if you’re having space issues in your very limited storehouse, you can use a Mercator to trade goods. You can trade two types of goods (buy two, sell two or buy one and sell one) with the bank at a fixed price. Lucky you if you secured some cloth cities, at seven sestertii per unit selling cloth really keeps the debtors from your door.

That’s what you can do on the board, but where is deck-building I was talking about before? You get to that part with a Senator card. It lets you buy one or two of the seven open cards. Card prices also come in two parts, one is printed on the card, the other on the board. Both parts are to be paid in goods, but the price on the board is lower the further along the line of cards you go – meaning that you can wait for the cards you want to have a reasonable price, if you want to risk losing them to someone richer than you. Newly bought cards do not go into your discard pile, like in most other games. You take them to your hand and can play them on your next turn.

Your starter set of cards is not especially large and only has one copy of most cards. If you really need an action that you already played, the Diplomat might be able to help. The Diplomat copies the action of a card that is on top of another player’s discard pile. Generally useful, but even more so when your opponents have bought cards that you don’t have, because you can copy those, too.

And finally, when you either played all your other cards or really need one of those cards that you already played back, you have the Tribune. His job is to bring all the cards you played back to your hand. He rewards long-term planning, though: for every card taken back beyond the first three, you gain a coin. As a side job, the Tribune can also recruit a new colonist in in Rome. Spending the goods for that pays of in three ways: you have another colonist on the board, your colonists are faster because every colonist on board is also worth a movement point, and it frees up a precious space in your storehouse, where unused colonists lead a sad and lonely life in the dark.

Those are the basic cards from your starter deck, but some more are available for purchase. The Colonist lets you put a colonist on the board in any city you have a house in, not only in Rome like the Tribune. The Consul is another way to buy new cards. He can only buy one card at a time, but doesn’t pay the price on the board, only the card price. Early access is valuable. Finally, the different specialists (Mason, Farmer, …) let you produce one type of goods in all your cities.

The real trick about all those cards, however, is not in what they can do. It’s in the combination of what they can do with the points they score. All cards have, besides their Character, one of the Roman gods printed along the bottom of the cards. When the game ends, either because a player ran out of houses or because the last card has been sold, the gods award you points. That’s not a euphemism for “you win by luck”, the gods literally award you points. Jupiter, for example, awards you a point for each house you built in a city that doesn’t produce bricks. I don’t know what the big man has against bricks, but he doesn’t like them. So, one point for each non-brick city, and that’s for each Jupiter card that you have. Similarly, Saturnus cards are worth a point for each province that you have a house in. Again, that is per card.Having six cards of the same god, and an acceptable score in his domain, brings in the big points.

Some may say that Concordia sounds like a typical point-salad game: everything you do scores points somehow, and in the end someone wins. But nothing could be further from the truth. It’s true that you score points for everything, but you have a lot of control over how many points you score. Picking a strategy early and seeing it through to the end is essential in Concordia, because having all your houses on the board doesn’t make you win unless you have a hand full of Jupiter or Saturnus cards as well. Or better yet, both. Those Card Gods really drive the whole game, and what cards you pick affects more than just your available actions.

The cards you buy early may also signal your intentions to the other players, and for a game with no direct interaction between players there are plenty of ways to mess with your carefully laid plans. Buying cards that you need before you have the chance, settling in the cities that might give you points to make them expensive for you, blocking access to cities with colonists, there are many options to stand in your way. But in the same vein, there are options for you to anticipate and counteract that. Play your cards right, keep a close eye on what the others are doing and buying, and especially keep an eye on your priorities. If something is not necessary, then don’t do it, because you may miss that one turn you took later in the game, or may not have the card you used in a more urgent situation.

Concordia is a tight game, with the maximum number of players (four on the Italy side of the board, five on the Imperium side) there is very little space and you will stand in each others way a lot. Especially the Italy side with four players has cut-throat competition. Concordia is also a very variable game, the cities’ produced goods are different for each game, affecting the province bonuses and making one game potentially very different from the next. But the real beauty of Concordia is that, from the ridiculously simple rule of “play a card, take that action”, it creates a wonderful strategic complexity with many options and strong interaction. I’ve been a fan of Mac Gerdts’s games for some time, but Concordia with it’s simplicity of rules and complexity of strategy is a real masterpiece and a very strong contender for this year’s Kennerspiel des Jahres award.

Thanks for this excellent overview and review, Kai. I must admit that I’ve been turned off by the box art for this game (shallow, I know, but it’s the little things…), but after reading your description, Concordia sounds really innovative, easy to play, and involving lots of interesting decisions. Thanks!

I’m glad you found the review helpful! As you can see from our photos, the lady on the box is not representative for the game inside. There’s not much illustration on anything, but the game board with pieces on looks vibrant and colorful.

And even if it didn’t, this is definitely a game you want for its inner qualities =)

Absolutely–the photos you posted of the board and cards look great. And that’s a good point about the inner qualities.