| Strategy | Luck |

|---|---|

| Interaction | Components & Design |

| Complexity | Score |

There are things in life you never really appreciate until they are gone. Eyebrows, for instance.

-Unknown alchemist

Depending who you ask, alchemy can be the attempt to create the Philosophers’ Stone, the quest to turn base metals into gold, the search for immortality, or, on less ambitious and more realistic days, the quest to not burn your eyebrows off and not kill any of your students with experimental potions. Alchemist Matúš Kotry invented another type of alchemy where he takes two things, both of them a good idea, and combines them to create a new thing. The two things he tried his alchemy with: boardgames and mobile apps. While both things on their own are nice, putting them together was a risky proposition because, lets face it, boardgamers tend to be purists when it comes to their hobby. For a long time, electronic components were to be found in kids’ games, and the few exceptions were not generally well received. On the other hand, successfully combining apps with boardgames is a sort of Philosophers’ Stone for game publishers and designers, it would open a host of new possibilities for game mechanics. Kotry’s Alchemists is the vanguard for a new wave of games combines with mobile apps. It’s closely followed by Fantasy Flight’s XCOM, IELLO’s World of Yo-Ho, and probably many more, but Alchemists was there first.

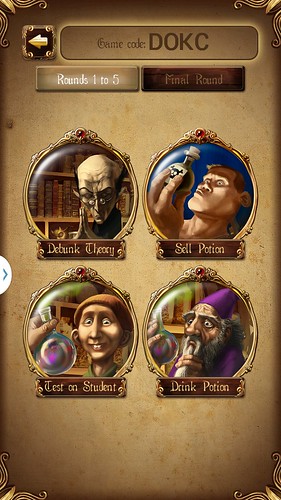

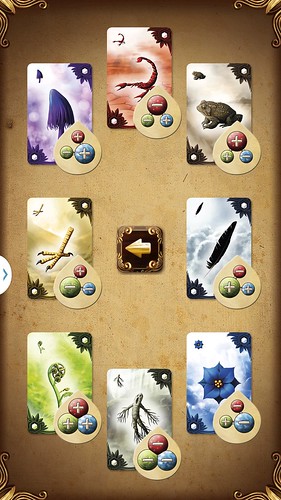

Alchemists combines a worker placement game with a deduction element. The worker placement is all traditional boardgame, no electronic support required. The mobile application – available for Android, iOS, Windows and as a plain old website – covers the deduction part. When a game starts, the alchemists are completely in the dark about what the mushrooms, flowers and toads they use as ingredients actually do. They have to experiment, mixing two ingredients into a potion and seeing what it does – commonly by feeding it to an unsuspecting student. Those experiments are done with your phone’s camera. The app recognizes your two ingredient cards and tells you what potion they make. The image recognition works very well, by the way, as long as the three white markers on both cards are visible the ingredients are reliably recognized within a second. Deduction games obviously existed before mobile apps, traditionally often implemented with hidden cards, but it would be hard to have the same level of subtlety that Alchemists has. The deduction part is not as simple as combining two ingredients to create a potion. Each ingredient corresponds to three aspects, each of which can be positive or negative. Combining two ingredients with a positive red aspect will create a Health Potion. That means that, when your experiment yielded a Health Potion, you can be sure that both ingredients were red positive, but it tells you nothing about their other aspects. It’s actually slightly more complicated than that, but you get the idea. Depending on what action you take, you might get less information that that, too. It would probably be possible to come up with a system of cards that does the same thing, but it wouldn’t be fun to use. The mobile app makes it easy and fun – although you still have to think yourself to come to the right conclusion. Final point about the app, you can play the same game on multiple phones simply by sharing a four letter code. No messing around with networks and game servers, just type four letters and everyone can use their own phone.

However, all that new technology is good for nothing if the game around it isn’t fun. What do you actually do in Alchemists? As stated above, it’s a worker placement game, so you place workers to take actions. You place your workers in an order set up at the start of each of the six rounds where you decide how early your alchemist gets up. Getting up late offers some bonuses – Ingredient cards and Favor cards that improve some of your actions or even give you additional actions. Getting up early, on the other hand, lets you place your workers last and take your actions first. Other players can not put workers in your spots, so there is no downside to placing last, but the upside of knowing what everyone else is doing, and you still take your actions first, so no one can get in your way if you just get up early enough. Most actions can be taken twice per round by each player, but some of them may take more than one worker for the second time. It sounds a bit convoluted, but you don’t have to think about it much while playing, it just works.

The actions themselves, at least the ones available right from the start, are simple enough as well. When you forage for ingredients, you take one of the five open ingredient cards, or a hidden one from the stack. To transmute an ingredient into gold, you discard that ingredient and take a gold coin. Yes, you can create gold in Alchemists, but it’s considered a waste of time and ingredients, a good alchemist can always make more money selling potions. Transmutation is an act of desperation. With the gold thus created – or gold earned in a better way – you can go buy Artifacts. Those rare, expensive items are worth victory points and mostly have other effects, too. Buying a Magic Mortar, for instance, lets you keep half the ingredients from every potion you mix. For the whole game, there’s a total of only nine Artifacts available, so if you want to collect them you should get up early.

The final two actions are the more interesting ones because they are where you get to experiment. Why are there two actions for that? Because with one of them, you test the resulting potion on an initially willing student, with the other action you drink the potion yourself. Both actions mostly work the same: you put two ingredients in your kettle and use your phone to find out what you created. The other players always see your result, but not the ingredients used, although they might be able to guess if they remember what ingredients you had. The difference between the two actions is what happens when you mix a negative potion, meaning one that combines two ingredients sharing a negative aspect. If you tested your potion on a student, you severely curb his enthusiasm and he can only be convinced to participate in more experiments through bribery: all other experiments this round, by you and by other players, will cost one gold coin for each bad potion the student already tried. A nice trick for early risers to piss of everyone else is to mix a known bad potion here before anyone else has a chance, making sure they all have to pay. Hey, no one likes morning people anyway, so what have you got to lose? If you drink the potion yourself, you will suffer from the effects and lose a worker cube for the next round, be forced to get up last or lose a point of reputation (Potion of Insanity, may lead to naked dancing in the town square).

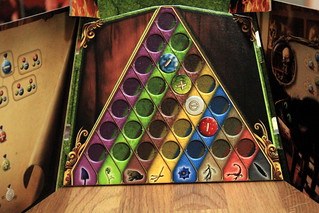

Whichever way you got your result, you mark it on your alchemical workbench, a matrix in your player screen. At the intersection of the ingredients, you place a marker showing the potion created. The workbench is a nice idea, the matrix standing in your player screen instead of lying flat saves valuable table space, but this part of the game doesn’t work as well as it could. The markers don’t fit into their holes easily and leave you with two options: either you force it in, which has the risk of making another one pop out, or you just place it loosely and it may fall out when someone bumps the table. Ultimately I would have been happier just marking my potions on a piece of paper – that you still need anyway, to mark the correspondence from aspects to ingredients.

Those are the actions for the first round, but starting with round two things get more complicated. There are three more actions then, and all of them are more elaborate than the round one action. The first is to sell potions. Every round, there will be an adventurer in town looking for a number of specific potions, and you can be just the alchemist to supply him. Don’t worry to much if you don’t know the exact recipe he or she is looking for, if the price is right adventurers will settle for less. The exact price will depend on the guarantee you give. At the top of the list, you can guarantee to make the exact potion wanted. That’s worth four gold coins, but make any mistake and you get nothing. One step down, you can guarantee a potion with the right sign, color unknown, for three coins. An adventurer looking for a Healing Potion won’t be ecstatic about getting Wisdom but he’ll be able to use it somehow. With even less confidence, you can guarantee to make a potion with the right sign or at least the neutral potion, also known as water. It might not be useful, but if you were looking for a good potion we can guarantee it won’t kill you. And finally, you can simply promise that the bottle won’t be empty and still earn one coin. You mix these potions with the mobile app as well, but the only output will be the level of quality you achieved. So you can experiment with your customers, but your data will be less useful than in an actual, controlled experiment. As if all that wasn’t difficult enough, selling potions doesn’t follow the regular player order. The customer never wants enough potions for everyone to make a sale, and you can offer a discount to move up in player order. Adventurers love bargain shopping. The discount is further modified by your current reputation – victory points – because adventurers also love to have confidence in the stuff they buy.

And then there are still the Theories, because one thing alchemists like better than money is the respect of their peers. To gain that, they publish their theories about the aspects of ingredients. Publishing a theory is simple enough, you pick an ingredient that no one has published about yet, a set of aspects that no one has published about yet, put them together and put your name on it. Thing is, just because you write about it doesn’t make it true, and you have to make a bet just how much you trust your own publication. If you’re really sure, then you put a seal for five or three points on a publication, and if someone proves you’re a fraud later, you lose points for it. Or you can publish before you are certain, and hedge against one aspect. The other two still have to be correct, but if the aspect you hedge against turns out wrong, you can just shrug and say you never said you were sure. Until someone disproved your theory, or the game ends, what you bet is hidden from the other players, which is fun because they can endorse your theory and put their own seal on it next to yours, while not knowing if you’re sure.

If, on the other hand, they think you’re full of it, they can debunk your theory. Using the app again, they select the theory to debunk, and which aspect they think is wrong, and the app tells them if the theory was right or not. If it was right all along, then the failed debunker loses a point and that’s it. But if the theory was wrong, then the seals on it are revealed, everyone involved loses points, the debunker gains points and may have the option to immediately publish his own theory. At least, that’s how it goes when playing the Apprentice variant of Alchemists. But the game does have two levels of difficulty, and the rules for debunking are the main difference. When playing on Master level, you can not only debunk a theory, but you can demonstrate a conflict between two theories. Doing so doesn’t debunk either of the theories, it just shows they can’t both be true. That’s bad for the original publishers because they can not go to conferences any more with those publications, and that might cost them a couple of points. Master Debunking is the most complex part of Alchemists, and most players will probably be happier playing with the Apprentice rules.

The game goes on for six rounds and ends with the Grand Alchemical Exhibition where each player gets to demonstrate the recipes they discovered for some final points of reputation – if they remembered to save ingredients, it’s a common mistake to arrive at the exhibition with empty bags. To get to this point will probably have taken you two hours – more if this is your first game – and you will probably have enjoyed it. But you’ll also feel mentally drained and ready for some Cards Against Humanity, because Alchemists is a hard game. It’s not even the deduction part, that requires some thinking but you quickly get the hang of it. It’s the deduction part, plus the strategy of worker placement with constantly scarce resources, plus the rather complex rules for some of the action. While I really enjoy the first two parts of it, I wonder if the game as a whole wouldn’t be even better if the rules had been a bit simpler. It’s a very good game, but maybe it could have been designed for more simplicity. It would still have a combination of deduction and worker placement that works well, and it would still combine a boardgame with a mobile app in a way that works remarkably well, but it might take less than an hour to explain to new players. But if complexity is what you’re looking for, then Alchemists is perfect for you. And it definitely drives home the point that games and apps can be combined in a way that is fun and useable, not doing something that could easily be done with traditional components, not just there to be all hip and modern, but a useful and unobtrusive part of the game. Integrated as the two things are here, I’m looking forward to more games with companion apps.