| Strategy | Luck |

|---|---|

| Interaction | Components & Design |

| Complexity | Score |

On the bigger gaming weekends, we sometimes have problems finding games to accommodate all the people. You know the scenario: there are eight to ten people and everyone wants to play with two other people and it becomes completely impossible to split into two groups. Now your options are limited. You can always play party games, of course. Sometimes it’s fun to guess words that someone else is dancing, but it does get boring. Or you dig out one of your boardgames that can fit eight people and prepare to spend five hours on it because most of those increase playing time with every additional player. Or you can try Masters of Commerce, with enough space for eleven players and nearly constant playing time.

It also takes less than five minutes to explain. Players are assigned one of two roles, landlord or merchant. This is not a team assignment, quite a contrary: landlords compete with the other landlords just as merchants compete with each other. Always two winners there are: a merchant and a landlord. Masters of Commerce has nothing to do with the masters of the Jedi, but opportunities to paraphrase Yoda are too rare to pass up. What each role does is nicely summed up with their names and hardly requires an explanation: landlords own properties – three at the start of the game – merchants rent them to do business.

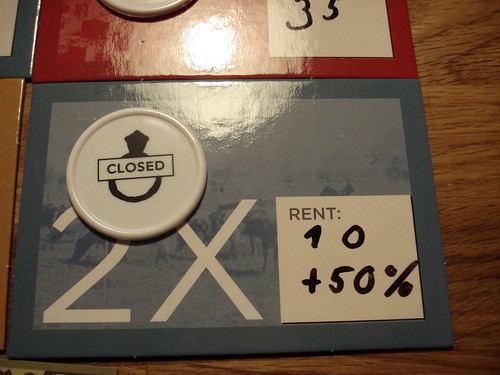

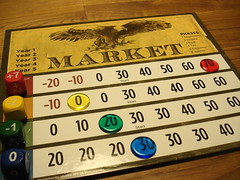

The core of the game is a simple and straightforward two minute period of negotiation. Everyone yells across the table, merchants try to rent shops while landlords try to fill theirs with tenants. When a landlord accepts a tenant, he writes down the rent on the property and places the merchant’s token on it. But until the two minutes are over, anything goes: when a better offer comes along, the landlord can just hand back the token and accept the new rent offer from the new tenant. Similarly, the merchant can take back his token and leave the property empty. The rent does not have to be the only subject of the negotiations, either. It’s the only thing that is enforceable, but everything both parties can agree on is fair game: cheaper rent in return for taking a less popular property as well, paying 50% of the merchant’s profits as rent, whatever you can think of. Deals are final the moment the time runs out, not one moment earlier but not one moment later, either. I strongly recommend that you use a timer with a bell instead of the hour glass included in the box – no one looks at it during the negotiations, anyway.When the negotiations are over, it’s time to do what everyone should like best in a game subtitled “Unleash your inner capitalist”: get out the wheelbarrow and bring in the money. The landlords know how many yachts they’ll be able to buy at this point, all the rents are fixed. The merchants are not quite so fortunate: their income still depends on the forces of the market: the dice. This is where the colours of the properties start being interesting. Properties come in four colours corresponding to the risk of doing business there. Blue properties have the lowest risk: they will always pay at least $20.000 and their profit can only change by $10.000 in one round. On the other end of the scale is red properties. In a bad economy not only don’t they make any profit, they lose $20.000. And they can go from one end of the income bar to the other in just one dice roll, you never know what they will give you. But in a good year, they make $70.000, almost twice what blue properties make. One dice is rolled to modify each colours payout, then merchants take their profit and – hopefully – pay their rent.

So far, the landlords could lean back and rake in the money, now it’s their turn to make some business decisions. Well, first they pay property tax, then they get to make business decisions: buy new properties. New properties enter the game through simple auctioning between the landlords, the merchants have to sit this part out. Now the landlords’ most priced possessions start showing up as well: double pay properties. The lucky buyer doesn’t profit directly – his rent is not doubled – but the prospect of double income for the tenant is a strong card in rent negotiations. After five rounds of this – the last one without a landlords’ auction as it would be pointless – the game ends with the richest landlord and the richest merchant as the two winners.

The dynamics of Masters of Commerce vary wildly from game to game, depending on a number of factors. The obvious one is the random economy, some games you end up rich no matter what you do, in other games only the blue properties make any profit at all. Another factor is the number of players: more players always means more chaos, but whether you’re playing with an even or odd number of people has a surprisingly big impact as well. In games with an odd number of players there are more merchants than landlords, producing a higher demand and giving the landlords a very easy time. With an even number, the landlords have to work much harder to not have their properties empty. Even outside those two factors, no two games are ever the same. Someone always comes up with a new idea how to close deals that forces everyone else to adapt.

While everything about Master of Commerce is about frantic interaction, there is one situation that slows the game down when it occurs: a merchant cannot pay his rent. We’re all certain that it will never happen to us, but sooner or later it will happen to someone, and then the merchant and his landlords have to come to an agreement. The default solution here is that the landlord gets to seize the income of one of the merchant’s shops next round. But if the merchant happens to fall in debt with another landlord before paying back that debt, he’s out of the game. But having one less merchant would be unpleasant for the landlords because of the sudden drop in demand for their properties, and since they don’t want that both parties will be interested in finding a different solutions. Those negotiations can take some time the other players are not involved in, but that’s the only real downtime you get in Masters of Commerce.

On a side note, Masters of Commerce has a very useful side effect for the players: you finally get to understand capitalism. All those times you were thinking “who would invest in that, everyone knows the price is inflated”? You’ll understand how those things can happen after you lost all your money on red properties that you just invested in because everyone else was making a fortune with them the previous round. Bubble economy on red: we had that. Economic crisis so bad that landlords had to sell some of their starting properties to be able to pay taxes? Yeah, we did that. Masters of Commerce makes a point in the current discussion about capitalism, but it’s anyone’s guess if it’s in favour or not.

If you are anything like our test players you’re probably thinking “okay, that sounds a wee bit boring” at this point. I think all of them said something along those lines. But if you’re anything like them, you will also discover that you’re having a great time around the middle of round two. All of our test players certainly said that. Even those with little interest in economics – like yours truly – were enjoying themselves immensely because playing Master of Commerce is a completely new experience. Negotiations have been part of games ever since people came up with games for more than two players, but the simple addition of a time limit to the negotiations made the whole concept new and exciting. You’re not closing complex treaties as you would in Diplomacy, you’re making more simple decisions, but under a lot of pressure. The atmosphere is not so much “diplomatic meeting” as it is “Wall Street trading floor”. Actually, if you think to any movie depiction of stock market trading you have a pretty clear idea of what was going on around our gaming table. That also means that Masters of Commerce is one of those games that might make your neighbours knock on the wall and yell at you to quiet down. But at least you can offer them a seat for the next round: there’s usually room for one more player, and there’s always time for one more round.