| Strategy | Luck |

|---|---|

| Interaction | Components & Design |

| Complexity | Score |

Oh yeah, Futuropia. Even that small kind of utopia doesn’t come for free, initially. Someone has to make it work first. Your mission, should you choose to accept it: build a condominium that produces its own food and energy and where all the work is done by robots.

Building an Achievable Utopia – How to play Futuropia

Futuropia is an optimization game with an easy goal: have a self-sustaining condominium in terms of food and energy, and have as many inhabitants as possible just follow their dreams instead of having their living souls crushed for eight hours a day.

As the game starts, you’re already halfway there. Your initial condo houses three people and produces all the food and energy they need. Their souls are still being thoroughly crushed, all three of them have to work on the generators to produce their resources, but hopefully we can change that.

Your options to improve your residents’ lives are limited. You have five action tiles, each round you flip one of them to take the corresponding actions. You only flip them back to re-use them after you either used all five, or after paying one resource for every action you didn’t use yet.

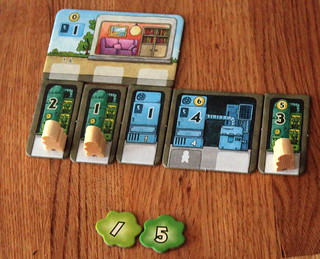

Out of those five actions, four are linked with a trial run of your condo’s systems. When you buy food or energy generators you’ll test the production of that resource, when you invite new residents you’ll test your food consumption, when you buy robots you’ll test your energy consumption. Your condo doesn’t have to be self-sustaining at every step of the way. You can and will buy missing resources when testing consumption. It’s only at the end of the game that you don’t have this option.

So, how does that work? When you buy a food or energy generator, first you pay the price. More on that in a second. Then you fire up all the generators of that kind that you have workers for, either human or robotic, and each gives you a number of food or energy tokens. Simple, right?

Generator pricing is just as simple, but pricing and technological improvements make a clever mechanism together. At any given time, you have two models of generators to pick from, current generation and next generation technology. Each model of generator has a base price, but on top of that there is a price modifier. It starts out at +/-0. Whenever someone buys a next gen generator, the modifier moves up and makes next gen generators more expensive and current generation ones cheaper. When the supply of either generation runs out, it’s time for the next next generation. If the stack that run out was the boring old generation, this also resets the modifier to +/-0. Simple, but a very effective mechanism to keep older hardware interesting.

Just like the two actions to buy generator, the actions to get residents or robots are symmetric. You take either take residents and then supply all your residents with food, or you take robots and then supply all your robots with energy. One difference is that, when taking residents, you may also acquire extra living space. One payment and its yours, none of that tedious waiting for things to be built.

The last action is the only unrealistic one. When you need more money you use the last action to receive subsidies – as if any government would spend money for us to get off the hamster wheel. Laughable. Even more unbelievable, they keep giving more money the more people ask. The payout increases every time someone takes this action. It’s a good thing the government pays, though, because the only other way to get money is through loans you’ll pay interest for until you can pay them back.

Those are the basics. Play continues until you put the highest tech generators into the market or one player has twenty-five people living in their condo. When either of those things happen, all players flip their action tiles face up and keep playing until they are out of actions or voluntarily quit. Count points, and done.

That’s the basic game. Once you’re familiar with it, Futuropia has two advanced levels to explore. In the upgraded game your starting condominium doesn’t have living space, so you’ll have to spend money early to get your project going. You’ll also use some of the special living quarters with extra effects for their owner. Those quarters can produce extra energy, extra food, let you convert between the two, receive higher subsidies, and more. Supply is limited, though, so you won’t have too many of those at once.

The expert game adds another variable element with tiles that change the rules. Each game you’ll have two of those in effect. They might give you less space to build generators, exchange generator models for special ones, make loans more attractive or subsidies less so. Which tiles you get is random, but fixed at the start of the game, so it doesn’t invalidate Futuropia‘s claim to no randomness.

I love living there, but what about building it? Our Verdict

As you may have glimpsed from the rules above, Futuropia is a very focused game, for better and for worse. It’s about building that condominium, stock it with generators to supply food and energy, all to have people live there with no need to sell their labor.

It’s one number to optimize, the number of people who don’t have to work. In a way, Futuropia is the opposite of many recent games. It’s become fashionable to boast about the many ways to victory. Futuropia doesn’t do that. There is one road to victory, everyone knows it, and the winner is the player who did it best. Personally, I prefer a wider game with more diverse options, but I can see the appeal.

My personal preference aside, there are two things I very much appreciate about Futuropia. One is the complete absence of randomness during the game. It’s an optimization game as pure as they come, and those just don’t work with rolling dice or drawing cards. The other thing is the randomness in the setup. Thanks to special living quarters and changing rules you can’t just follow the same strategy every time and be sure it works. Those two things together really make Futuropia work.

Would I recommend it, though? Not for everyone. You do end up doing similar things with minor variations every time you play. I know some of you enjoy that, finding a way to squeeze the absolute best out of a simple system. You are the kind of player Futuropia was made for. If, however, you’d rather try a completely different approach every time you play, then you might want to skip this one.