| Strategy | Luck |

|---|---|

| Interaction | Components & Design |

| Complexity | Score |

The game lets you work on four construction projects: obelisks, burial chamber, temple and pyramids – at least the last of which is closely tied to Imhotep, he is credited with designing the first pyramid, and he probably built a bunch of the other things, too. But building those things is not the big problem of Imhotep, that’s really just stacking things on top of each other. But have you ever wondered where all the stones came from, when all you see around the pyramids is sand? That’s the real challenge in Imhotep, to get those giants blocks of rock down the Nile when the other players want to do the same.

In each of the game’s six rounds, there are four ships of different sizes to carry stones down the river. First they have to get from the quarry to the river. For your action on one turn, you can load three stones on your supply sled. Loading a single stone into a ship takes up a full turn as well, and it doesn’t make the ship your property. As long as there’s space, anyone can load in their stones. Even worse for your ability to plan, when the ship has reached its minimum load anyone can use their turn to take it to one of the construction sites, regardless of who’s stones are in that ship. They don’t even need any of their stones there – a big deal, as we’ll see shortly – the ship just needs its minimum load and the dock at the destination site cannot have another ship docked this round.

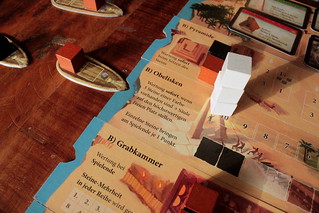

When a ship arrives, the stones are unloaded and built into the local construction project. How that happens and what is the effect is different for each of them. It also depends on whether you play the simpler A-side or the more complex B-side – I’m going to talk about the B-side here, because that’s what you’ll end up playing after the second game, anyway. The pyramid site has three small pyramids with four spaces at the bottom, one space at the top – quite obviously only available after the bottom is built, Imhotep didn’t invent anti-gravity. Each stone’s owner decides which pyramid to place it in, not an unimportant decision since every space is worth a different number of points and may bring with it another bonus, like the ability to immediately load stones on your supply sled.

Everything at the pyramids happens immediately. At the second site, the temple, you only get something at the end of each round. The temple is a simple wall with five spaces that have to be filled in order. When one row is full you start stacking another one on top. The points and bonuses for each space go to the player who’s stone is on top there – especially useful since three of the spaces let you load stones on your sled for next round. The next site, the burial chamber only scores at the end of the game. There are three rows of stones, and for each row points are awarded to the player with the most stones. Getting those majorities needs some good planning because the ship here is unloaded by column. Finally, at the obelisks, nothing happens until a player has three stones there, then he stacks them up and scores, more points the fewer players already built an obelisk. (We call this part “the tiniest Jenga” because our obelisks tend to fall over…)

And finally, there is one more site to dock your boat that is not exactly a construction site: the market. Going to the market and using giant blocks of stone as currency doesn’t exactly sound convenient, it actually contradicts a major reason for inventing money in the first place, but that’s exactly what you do. You can either buy one of the three open cards for this round, or you buy the mystery pile of two hidden cards and keep one of them. Those cards have some pretty nice things. Statues score points at the end of the game, more points the more you have collected. Other cards let you immediately place a stone somewhere, score extra points for every stone at a site or cards you play for special actions.

Imhotep is a game that lives on interaction, for better and for worse. Sure, figuring out where you score the most points is part of it, but what makes Imhotep interesting is that you have to figure it out with ships that you share with the other players. You want to get your stones to the right places, at the right time, and with the right players’ stones sharing your boat. You obviously want to take all the ships to where they score the most points for you, but accomplishing that is not as easy as it sounds. But it’s so satisfying when you can force two other players to complete the bottom part of a pyramid so you can place two capstones for four points each. But the shared boats are also the “for worse” part of the interaction, because you’ll often find yourself playing to deny other players their points instead of playing to score yourself. When two players have managed to prepare a ship together that will score them both big points at the right site, then your best best course of action is often do abduct that ship to another site where there stones aren’t worth as much. And if that site just happens to be where yet another player could score high and now you blocked the dock, all the better. I know that many will take that as a tactical challenge – I do – but it is a rather negative interaction, and one that is impossible to avoid if you play to win. Because of the interactivity, Imhotep works better in three or four players than in two, by the way.

Despite the warning, I really enjoy Imhotep. It’s not a complex game, even playing the B sides, as you probably guessed from it’s nomination as Spiel des Jahres and not as Kennerspiel. But it has a good tactical depth and creates a lot of interaction without direct trade or negotiations between the players. I don’t enjoy Imhotep quite as much as its competitor Codenames, but I would be perfectly fine with seeing it as Spiel des Jahres 2016.

Tom Vasel going to love this. He seems to think, since he has thrown away more games then most people will every own, nearly ignoring not everyone has played an Egypt themed game, no game , for evermore, should be so themed again.

I have played exactly one, Ra.

And what’s not to like, it support ages 10-199 :)