| Strategy | Luck |

|---|---|

| Interaction | Components & Design |

| Complexity | Score |

“What, another coop game?”. Yes, I can hear the groans from over there. It’s another cooperative game, although we had Space Alert and Ghost Stories only recently. But don’t worry, all you people that want to stab your opponents in the back will see games for you again soon. Actually, Shadows over Camelot is not such a bad choice for you, there may be a traitor among King Arthur’s loyal knights.

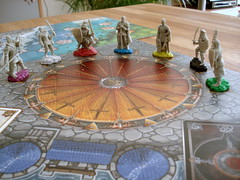

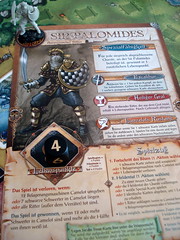

Shadows over Camelot is, before you know anything else about it, a very beautiful game. The game boards – yes, more than one – are lavishly illustrated, some even on both sides. So are the different kinds of cards and the seven knight’s character sheets. On top of that the game contains individual plastic miniatures for Arthur and the six knights, for the three relics you can acquire in the course of the game plus a bunch of siege engines, Picts and Saxons. All miniatures are grey (apart from Arthur’s and the knight’s bases in player colours) but nevertheless look good, and the experienced miniature painter – so definitely not me – can fix them up easily enough.

To start the game, each of the up to seven player draws one character sheet to select his hero: King Arthur or one of the Sirs Gawain, Galahad, Kay, Palomides, Parcival and Tristan. There is no word on what brave Sir Lancelot and Sir Robin The-not-quite-so-brave-as-Sir-Lancelot are doing at this time. (You just encountered one of the biggest risks of Shadow over Camelot: death from an overdose of Monty Python and the Holy Grail quotes). It is also at this point that you find out if you’re the traitor. Every player receives a loyalty card from the set of eight, one of which is the Traitor – even with seven players, you can’t be sure if there really is a traitor among you. Thematically, the loyalty assignment is a tad dubious since it can make Arthur himself a traitor against his own cause. But lets not nitpick those thematic details, the dark side traditionally has cookies and cookies can sway the mightiest king.The basic structure of the game is similar to most other cooperative games: there is many more ways to lose the game than there is to win, and evil always goes first. So, on each turn, the players first choice to make is which poison apple to bite:

- lose a point of life, which are easily counted using six-sided dice. So even when you’re brimming with life, this option is 16.666% bad.

- put a siege engine in the fields before the gates of Camelot. When twelve machines are assembled there – and there’s plenty more ways to collect them – then Camelot’s enemies have taken the castle and the game is, unsurprisingly, over.

- draw and execute a black card.

The standard option, given the limits of your health and the limited space for siege engines, is the black card. Most of the black cards simply work against the Knights of the Round Table in one of the various quests they may embark on. Some of them, however, come with even worse effects on the cards: for example, Mordred will support the Picts or Saxons and make them harder to defeat, Vivien prevents Merlin from helping the knights and Morgana has more evil tricks up her sleeve than you can shake an Excalibur at.

After the dark side had their fun, it is time for heroism. The players actions in Shadow over Camelot all relate to the various quests. Quests are, in turn, related to the locations on the game board, have different conditions for victory and defeat as well as different rewards and punishments. Some quests can be done in groups, some need to be completed alone and some have to be completed multiple times.

Rewards and punishments mostly vary in quantity between the quests: winning or losing health is common, as is drawing cards as a reward. All quests also place from one to three swords on the round table in Camelot, white ones for victory and black ones for defeat. These swords are another way to lose the game, and also the only way to win: if, at the end of the game, more than half of the twelve swords are white, the game is won. Three of the quests also reward a powerful relic when victoriously completed: the Holy Grail, Excalibur and Lancelot’s Armour, all with powerful effects to help their bearer.

What is to be done to succeed on a quest is different for each. The Grail and Excalibur quests are, basically, tug-of-wars for the respective relic. Playing any white card on the Excalibur quest or a Grail card on the Grail quest brings the Knights of the Table one step closer to retrieving it while black cards concerning that quest take the relic one step away. The other quests are “combat quests”: here the players play white number cards in different combinations – a Full House for the Lancelot quest, three different Three-of-a-Kind for the Dragon quest and a Straight from one to five for the wars again Saxons and Picts. The two war quests are opposed by time alone: if they are not completed before four miniatures are put on the battlefield, the attackers break through and drag their siege engines to Camelot. The other quests are opposed by black cards: the cards for this quest also have a numeric value, and when the quest is finished – either because the player card spots are filled or because the black card spots are filled – the sum of the player’s white card values has to surpass the black card’s sum to be victorious. Camelot, as a location, is slightly special. While there you can try to rid the battlefield of a siege engine, but you can also draw two white cards here – other than completing quests this is the only reliable source of fresh cards.

What can a player do about these quests, then? First of all, travelling to the right place is good. Unfortunately, travelling in the time of Arthur is perilous enough to count as it’s own heroic deed, so when you travel somewhere, that is your action already. Once arrived – rather, on your next turn – you may play a card to advance the quest. Number cards and the quest specific cards are straightforward here, as described above. Like the black special cards, players also get more powerful special cards, sometimes, if they’re lucky. These cards can heal a knight, draw fresh cards or aid on one of the quests – you still don’t get to play more than one. You can also just rest your legs and and lick your wounds for one turn – by the miraculous healing properties of saliva, this restores a point of health. Finally, you may accuse one of your fellow knights to be a traitor.

Treason is a serious accusation, and so are the consequences. The accused player immediately reveals his loyalty card – if only it were that easy in real life. If he is not the traitor, one white sword in Camelot has to be turned to the black side instead. If he was the traitor, however, a white sword is won.

Before he is thus revealed, the traitor plays just like any knight. His options to betray the loyal knights are limited at this point. Mainly, he avoids playing well. The only option to directly harm the other players is in placing black cards on the quests. Player can place these cards face down, hiding their strength from the others, and draw a white card in return. The traitor can hide cards with high number in this way and pretend they are harmless – the cards are shuffled before they are revealed, so if there was more than one hidden card on the quest, the traitor can do this without giving himself away completely.

However, after the traitor is revealed, his role becomes a more shadowy one: his knight is removed from the game and he can no longer participate in quests. Instead, on each turn he can steal a white card from another player and either play an additional black card or place a siege engine. If the traitor remains hidden until the end, it’s even worse for the loyal knights: at the end of the game, an unrevealed traitor can turn two white swords to the dark side.

So, as usual, many ways to lose and only one way to win. In that respect, Shadows over Camelot is not different from most other cooperative games. Beyond that, however, I do have issues with some aspects of the game. Playing in the Arthurian legend, one of the greatest epics of the western world just doesn’t feel very, well, epic. Even all the great game materials don’t hide the fact that you complete the quests by playing cards which were randomly drawn. The same is roughly true for other cooperative games like Pandemic, of course, but here the players influence on what they can actually do is much smaller since most cards only have a single use. What you can do, which quest you should go on is based on the cards you draw. And with little chances to exchange cards, you’re stuck with what you get. Playing only one card per turn is a bit tedious as well when you have all the cards you need available to you. On each individual turn, it just doesn’t feel like you’re making progress.

Also, there is very little actual change to the game. Sure, the state of the quests changes back and forth with every card played, but besides the three relics there is nothing that actually changes what you can do. You have the same actions available at the end of the game as you do at the start, you don’t gain new options. On the other hand there is no escalation to the game either – things just get worse at a steady pace, but the tension doesn’t really rise.

But there are things I like in Shadows over Camelot, beyond the neat knighples. The traitor mechanic is very well implemented here. Due to the fact that you never know if there actually is a traitor, everyone is kept guessing if the others are playing genuinely badly (or maybe have really bad cards) or are committing sabotage. The power the traitor gains when he reveals himself and the complete change of the game for him is a nice touch as well and was later adapted by Battlestar Galactica. The uncertainty about the presence of the traitor together with the penalty for a false accusation make “Are you really sure he is the traitor? Really really sure?” the heatedly discussed question around the table. The question is, however, not usually hot enough to replace the “But I could also do this, why do you think I should do that?” of other cooperative games, missing here because your cards determine your game too much.

It would be too much to call Shadows over Camelot a bad game. It has it’s high points, it looks great and a lot of people do genuinely enjoy it, according to their testimony. For me, however, luck plays a too big role here and too many of my decisions are made for me. I don’t doubt that, were Shadows over Camelot developed today, many of my points of criticism would be addressed. After all, it was published close to the beginning of the cooperative game upswing and doubtlessly inspired many things that came later in the genre. I just feel that some of the things it inspired are better choices now when looking for a cooperative game to play.